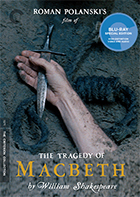

Macbeth [Blu-Ray]

|

Although it was the subject of much discussion and debate during its initial theatrical release in 1971, Macbeth is a film that now often falls through the cracks in discussions about both the career of director Roman Polanski and cinematic adaptations of William Shakespeare, which is curious because the film not only represents an apex of Polanski's darkest sensibilities, but it is one of the most fascinating of Shakespearean adaptations. When he made Macbeth, Polanski was at the height of his career, in complete command of his art; but, at the same time, he was in one of the darkest periods of his life, as his pregnant wife, actress Sharon Tate, had been gruesomely murdered by the Charles Manson family a mere six months before he began production.

Although it was the subject of much discussion and debate during its initial theatrical release in 1971, Macbeth is a film that now often falls through the cracks in discussions about both the career of director Roman Polanski and cinematic adaptations of William Shakespeare, which is curious because the film not only represents an apex of Polanski's darkest sensibilities, but it is one of the most fascinating of Shakespearean adaptations. When he made Macbeth, Polanski was at the height of his career, in complete command of his art; but, at the same time, he was in one of the darkest periods of his life, as his pregnant wife, actress Sharon Tate, had been gruesomely murdered by the Charles Manson family a mere six months before he began production.

Not surprisingly, when Macbeth is discussed, it is most frequently in relation to its violence. It is particularly intriguing that Macbeth was released in a year that is notable for a series of intensely violent and challenging films that, in different ways, questioned the very nature of violence: William Friedkin's The French Connection, Sam Peckinpah's Straw Dogs, and Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange. Like those films, Polanski's Macbeth challenges our unspoken comfort with mediated violence by directly confronting us with it; yet, the film is not discussed nearly as often as, say, A Clockwork Orange. However, Polanski's film is every bit as challenging, every bit as masterful, and every bit as meaningful and memorable. The prevailing characteristic of Polanski's Macbeth is butchery—the brutal and graphic literalization of every violent act in one of Shakespeare's most violent plays. Where the Bard left much of the gore offstage, Polanski brings it front and center. When Macduff (Terence Bayler) cries "O horror, horror, horror!" after seeing the murdered body of King Duncan (Nicholas Selby), we know exactly what that horror is because we have seen Macbeth (Jon Finch) do the deed that Shakespeare hid between Scenes II and III of the second act. While in Shakespeare's play Macduff is told that his wife and children have been "savagely slaughter'd," Polanski shows the savagery. We see Banquo's "gory locks" and the "twenty mortal murthers on his crown." Thus, the violence of Macbeth's ambition is laid brutally bare; no longer abstract, it is visualized by brutal stabbings from which the camera does not flinch. Similar to Akira Kurosawa's take on Macbeth, rightfully titled Throne of Blood (1957), Polanski also uses atmosphere to literalize the characters' sinister impulses and ruthless ambitions. Shot in stunning Todd AO widescreen by British cinematographer Gilbert Taylor (who shot Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove and had previously worked with Polanski on his 1966 film Cul-de-sac), Macbeth is a dark, gloomy film in which the Scottish highlands are rendered a muddy wasteland inhabited by lost souls. The darkness of the landscape is punctuated with flashes of lightning out of a horror movie and copious splashes of blood from slit throats and dismembered bodies. Considering the visual power of the film's violence and the despairing nature of its subject matter, it is impossible to discuss Macbeth without considering the Manson murders, as uncomfortable as that may make us. After all, how can one hear the lines "Your castle is surpris'd; your wife, and babes, savagely slaughtered" and not think of its relation to the midnight invasion of the Polanski home on Cielo Drive in Bel Air that left five people dead—mercilessly stabbed, shot, and hung? The trauma inflicted by that real-life slaughter deeply affected Polanski and his work, driving an already dark-minded artist into the kind of dreadful depths that few mainstream filmmakers dare tread. Polanski was, after all, coming on the heels of a major studio success with Rosemary's Baby (1968), his first American film project. He could have made virtually anything, yet he chose to adapt a Shakespearean tragedy. Even more importantly, he made it his own by turning Shakespeare's cautionary moral tale into a bloody requiem for humanity. If there is a theme in Polanski's Macbeth, it is that all hope is lost (Macbeth's line about life being "a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing" is particularly powerful here). Polanski drives this home by utilizing one of his favorite devices: narrative circularity. The film begins with the three witches foreseeing their encounter with Macbeth, and it ends with the new king's brother seeking them out, an addendum not in the original text that makes clear the unending circularity of humankind's thirst for power and its attendant violence. Macbeth's downfall is thus no longer a cautionary tale of would could happen; rather, it is but one example of what will happen. Polanski made Macbeth in between two of his masterpieces—Rosemary's Baby and Chinatown (1974)—and what is so intriguing about his take on the Bard's famous tragedy is the way it fuses the thematic underpinnings of those two films. Like Rosemary's Baby, Polanski's Macbeth draws its underlying dread from the suggestion that ordinary reality masks the presence of dark supernatural forces that prey on the ambitious and the greedy. In Rosemary's Baby, a supernatural gothic thriller set in modern New York, it was Rosemary, the young wife of a theatrical actor, who paid the price for his greed, whereas in Macbeth it is the title character, a Scottish lord whose ascent to power requires the spilling of much innocent blood, who pays the ultimate price. Like he did in Rosemary's Baby, Polanski brings the supernatural down to earth, presenting the clairvoyant witches not as fully supernatural beings who can disappear into thin air as they did in Shakespeare's play (which is filled with allusions to hell, demons, and the Devil), but rather as outcasts—some old and haggard, some young and attractive—who have sold their souls to the dark arts. In their repulsive visages we see the fate of Macbeth's twisted soul. The witches are but one level in which, like Chinatown, Macbeth presents a world that is capable of such depths of depravity, such unrelenting evil, that it is beyond our capacity to grasp it. In Chinatown, private dick J.J. Gittes stumbles into a mystery whose eventual solution confronts him with a kind of evil he is incapable of surmounting; in Macbeth, the title character is the embodiment of that evil. Unlike Shakespeare's tragic antihero, Polanski's Macbeth is corrupted from the start, lacking only the opportunity to quench his thirst for real power. Some have read this as a flaw in Polanski's retelling, as if the story has no real meaning unless Macbeth travels the descent from good to evil. Such a reading, however, denies Polanski's imagination, which uses Shakespeare's play as a framework for his own view of the world, one that was shaped as much by his experiences as a Jewish child in Poland whose parents were sent to concentration camps by the Nazis as it was by the Manson killings. To Shakespearean purists, this is heresy of the highest sort, but for those who admire Polanski's verve and artistic audacity, it is nothing less than the pinnacle of his commitment to exploring the darkest depths of human potential.

Copyright ©2014 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)

Subscribe and Follow

Get a daily dose of Africa Leader news through our daily email, its complimentary and keeps you fully up to date with world and business news as well.

News RELEASES

Publish news of your business, community or sports group, personnel appointments, major event and more by submitting a news release to Africa Leader.

More Information